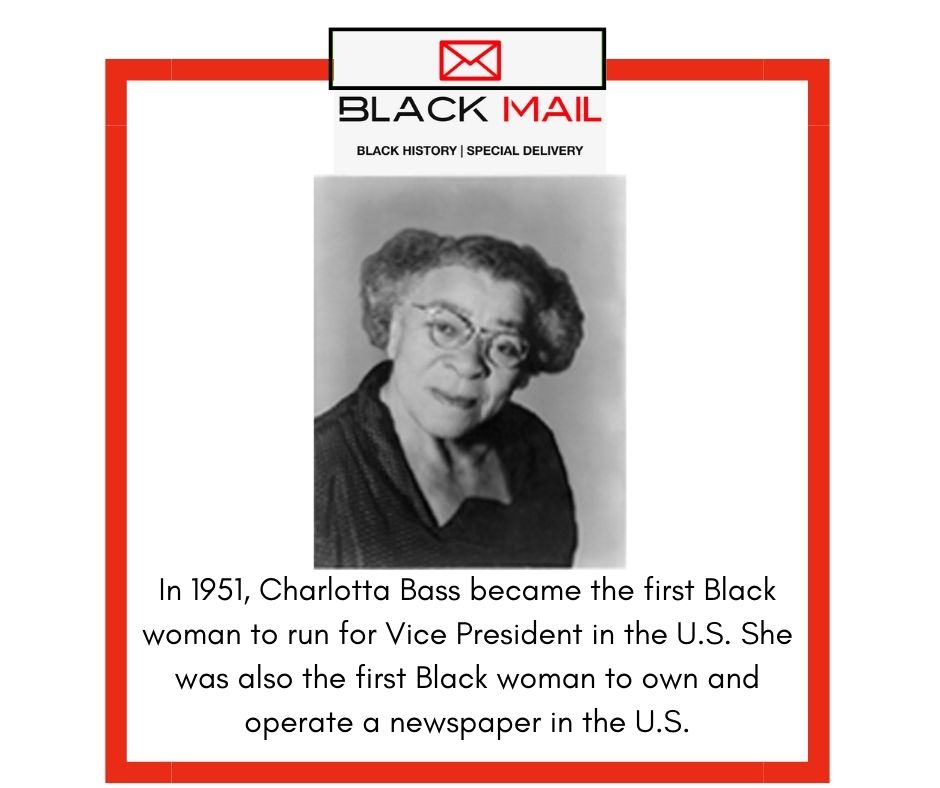

Welcome to Black Mail. Where we bring you Black History–Special Delivery!

Charlotta Spears Bass was the editor and publisher of the California Eagle, which was the oldest black newspaper in California during the first half of the 20th century. Along with her husband, she served as editor from 1912 until 1951. She used the newspaper as a powerful platform to confront racial discrimination and advocate for civil rights.

Apart from her editorial endeavors, Bass was a prominent social activist who led campaigns against employment and housing discrimination in Los Angeles and across the nation. She was also the first African American to sit on a grand jury in Los Angeles. Bass pursued political aspirations by running for positions in the U.S. Congress and the Los Angeles City Council, although she was not successful. Bass’s indelible mark on history was further solidified in 1952 when she made history as the first African-American woman to run for the esteemed position of vice president of the United States.

Charlotta Amanda Spears Bass, born to Hiram and Kate Spears in Sumter, South Carolina, was the sixth child among eleven siblings. While her exact birth date remains uncertain, she was likely born on February 14, 1874, although some sources suggest alternate dates of 1879 or October 1880. Little information is available about her formative years, although it is known that she received her education in public schools. At the age of 20, Bass relocated to Providence, Rhode Island, where she resided with her eldest brother, Ellis. During this time, she pursued higher education, completed one semester of coursework at Pembroke College, and also gained work experience in the office of the Providence Watchman newspaper.

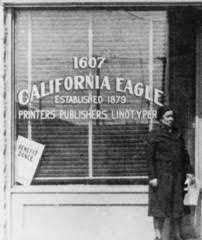

After residing in Rhode Island for a decade, Bass encountered health issues, prompting her relocation to California for recovery. Initially intending to stay for only a brief period, she ultimately settled there permanently. Upon arriving in Los Angeles, Bass secured employment selling subscriptions at the Eagle newspaper for a weekly wage of five dollars. In 1912, when the editor John J. Neimore’s health deteriorated, Bass was asked to assume editorial responsibilities. Following Neimore’s passing later that year, the paper was acquired by Captain G.W. Hawkins, a second-hand store dealer. Bass published her inaugural paper on March 15, 1912. At that time, the Eagle stood as California’s oldest black newspaper. A year subsequent, Bass purchased the newspaper for a mere $50 at a public auction, subsequently renaming it the California Eagle.

Under Bass’s leadership, the California Eagle upheld a longstanding commitment to combatting racial inequality and discrimination. During the early 1900s, California saw an influx of African-American migrants seeking improved economic prospects compared to the South. The burgeoning black community in Los Angeles experienced significant growth and boasted high rates of homeownership. Nonetheless, Bass and fellow African-American intellectuals, including W.E.B. Du Bois, were vocal in highlighting persistent discrimination despite the opportunities available in California. Bass struggled as editor, publisher, and distributor of the paper for a year until she hired Joseph Blackburn Bass to work at the form, first as a journalist and eventually as editor. Bass was a teacher from Kansas.

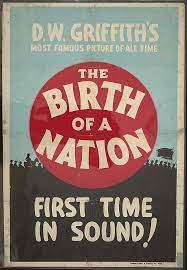

Bass had used the newspaper as a weapon in the fight for equality since becoming an editor in 1912. Bass’ activism reached a new level after the release of D.W. Griffiths’s film Birth of a Nation in 1915. The movie was based on Thomas Dixon’s novel The Clansman, and it portrayed black people in a very negative light. Bass formed a campaign to prohibit the production of the film in Los Angeles. She succeeded in preventing certain scenes from being filmed in the city, but she lost a court battle to stop the movie altogether. Part of the reason why Bass lost her campaign was that both black and white workers wanted to work for the film because Griffith was paying very high wages.

Bass’ willingness to battle the California film industry gained her national recognition as a social activist. Bass traveled to Texas, Kansas, Illinois, Massachusetts, and New York to speak out against racial discrimination. She was particularly concerned with discriminatory employment practices. In 1917, she fought the hiring practices of the Los Angeles Fire Department. Although African-American men were allowed to take the civil service exam, only white men were actually hired. Bass used the editorial column of her paper to raise this issue with the city government and the black community. According to Rodger Streitmatter in the Significance of the Media in American History, Bass wrote in the California Eagle that “the city of Los Angeles does not ask the color of a man’s skin when it presents its tax bill.” After a three-month campaign, Bass’ efforts paid off, and the city hired its first black fireman.

Bass’ next campaign was against the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors for refusing to hire African Americans to work in the county hospital. The hospital reluctantly agreed to hire black nurses’ aides only if Bass would interview and select the applicants. Bass agreed to the stipulation and screened applicants for a year before the county was convinced that the black workers were competent and Bass’ services were no longer needed.

In 1926, Bass organized the Industrial Council of Los Angeles to fight job discrimination, and she was elected the first president. In the 1930s, Bass introduced the “Don’t Spend Where You Can’t Work” campaign to Californians. The campaign had begun in Chicago in the 1920s, and it encouraged African Americans to boycott businesses that would not hire black workers. Bass used this campaign to fight large corporations. For example, she managed to convince 100 African Americans to cancel their telephone service because the Southern California Telephone Company did not hire black workers. The company gave in to the economic pressure and changed its hiring practices.

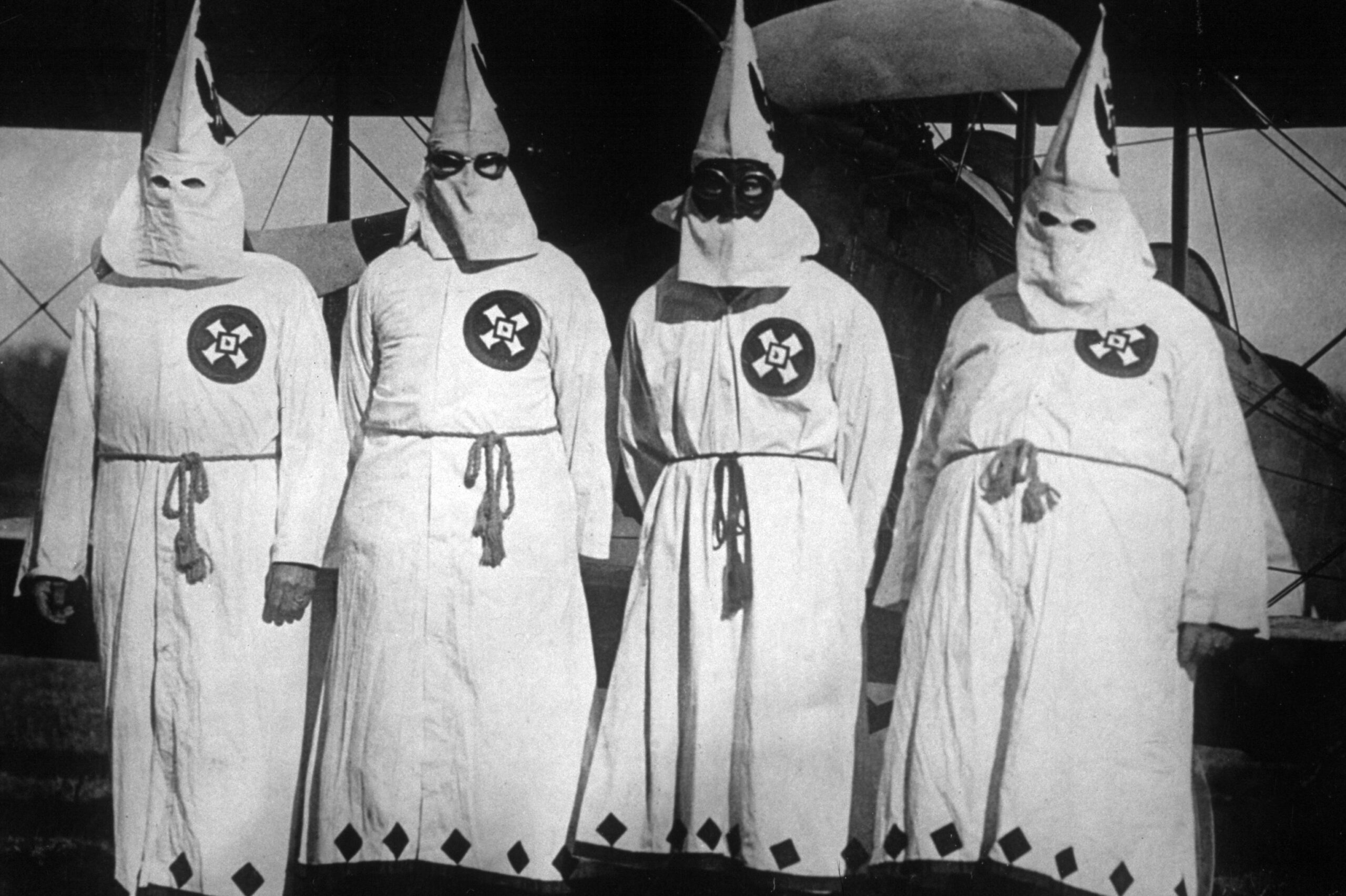

Bass frequently faced threats of physical violence due to her activism, particularly in the 1920s when she directly confronted the Ku Klux Klan. Through her newspaper, she courageously exposed the hateful practices of this white supremacist group, prompting retaliatory actions such as threatening phone calls and letters. In 1925, Bass further aggravated the Klan by publishing a letter signed by G.W. Price, the Klan leader in California, revealing a plot to falsely incriminate prominent black leaders for drunk driving to tarnish their reputation. Subsequently, the Basses were sued for libel by Price, leading to a legal battle fought in an all-white court. Despite prevailing in court, the Klan responded with renewed threats of violence. In one harrowing incident, eight hooded men confronted Bass at her newspaper office while she was alone. Undeterred, Bass boldly retrieved a firearm from her desk drawer, prompting the hooded men to retreat swiftly.

Bass believed fervently in the importance of the causes they championed, deeming them worthy of the risks involved. By 1925, the California Eagle had burgeoned into the most prominent African-American newspaper on the West Coast, boasting a staff of 12 and publishing 20 pages weekly. In the early 1930s, Joseph Bass’s declining health rendered him incapable of overseeing the newspaper’s daily operations. His passing in 1934 left Charlotta Bass solely responsible for managing the business. To bolster capital, she incorporated the newspaper and entrusted a board of directors with making pivotal decisions. Undeterred by her husband’s death, Bass persisted in her social activism. Notably, she campaigned vigorously for the integration of the Los Angeles Railway Company, successfully advocating for the hiring of its first black conductor in 1943.

Bass orchestrated a campaign to safeguard a cohort of affluent African Americans from eviction by white residents. Among these homeowners were esteemed individuals like doctors, lawyers, and entertainers, including actresses Hattie McDaniel, Louise Beavers, and Ethel Waters. Taking their plight to court, they secured the right to remain in their homes. Bass extended her advocacy to residents in middle- and lower-class neighborhoods, leveraging the newspaper to maintain public awareness of the issue of housing covenants. Finally, in 1948, the United States Supreme Court rendered racially restricted covenants unconstitutional.

Transitioning from Journalism to Politics In the 1940s, Bass embarked on a political career, channeling her social activism into public service. Initially a lifelong Republican, she grew disenchanted with the party’s stance on racial equality, prompting her to join the Progressive Party. Expressing her disillusionment at a Progressive Party convention in 1952, Bass articulated, “As a member of the elephant party, I could not see the light of hope shining in the distance, until one day the news flashed across the nation that a new party was born,” as quoted in Gerda Lerner’s book Black Women in White America. Contesting as the Progressive Party candidate for the U.S. Congress, 14th district, in 1944, and for the Los Angeles City Council in 1945, Bass, despite not securing victory, significantly elevated the discourse on civil rights. In 1948, she assumed the role of co-chairperson for Women for Wallace, a group advocating for the Progressive Party’s presidential candidate, Henry A. Wallace.

In 1951, after more than 40 years at the helm, Bass transferred ownership of the California Eagle to Loren Miller, an attorney and former reporter for the paper. Bass relocated to New York City to contribute to the national headquarters of the Progressive Party. The following year, in 1952, Bass was nominated as the vice presidential candidate for the Progressive Party. Teaming up with Vincent Hallinan, an Irish lawyer, they campaigned on a platform advocating for job security, housing rights, civil rights, and an end to the Korean War. Adopting the slogan “Let my people go!” for their campaign, they garnered less than one percent of the vote in the national election. Nonetheless, Bass etched her name in history as the first African-American woman to run for vice president of the United States.

Retiring after the 1952 campaign, Bass settled in Elsinore, California, dedicating her time to penning her memoirs, which were later published in 1960. Despite her retirement, Bass’s outspoken political stance drew attention from racist organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan and subjected her to scrutiny from the federal government. Accused of anti-American activities, Bass faced interrogation by the FBI for suspected ties to communism and was monitored by CIA agents during her international travels. Undeterred by threats to her safety or civil liberties, Bass remained steadfast in her commitment to advocating for racial equality throughout her illustrious career.

Another installment of melanated mail has been delivered. Ponder, reflect, and pass it on.