Welcome to Black Mail, where we bring you Black History—Special Delivery!

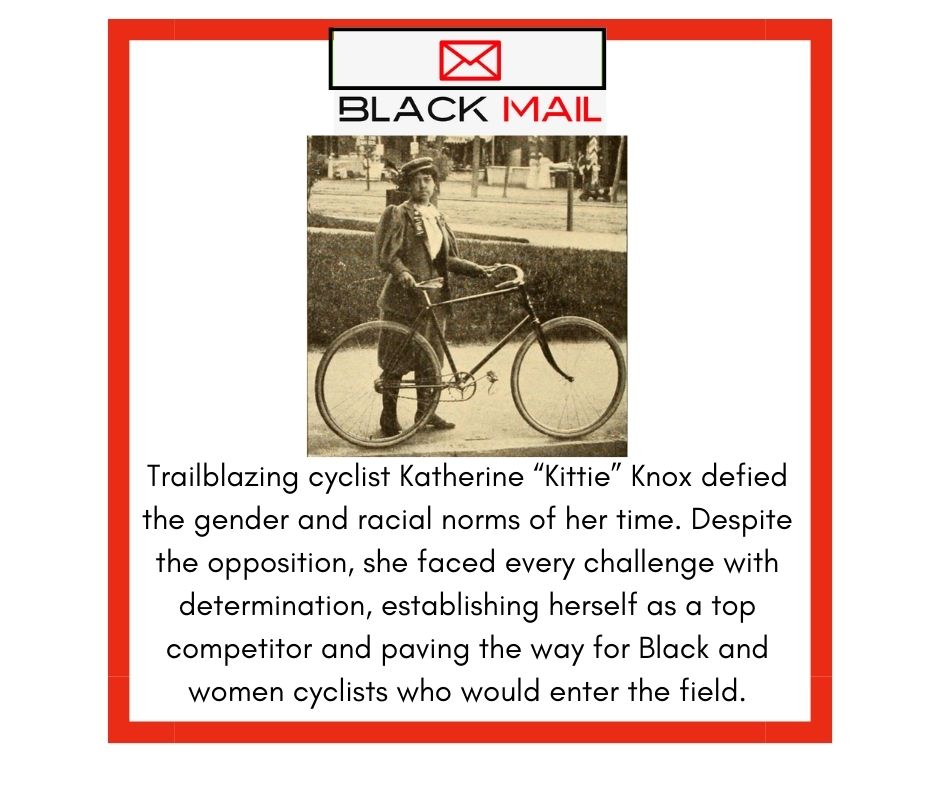

Katherine Kittie Knox defied 19th-century societal norms by participating in bicycle races and meets, defying racial and gender barriers in the sport. Born on October 7, 1874, in Cambridgeport, Massachusetts, she was the daughter of Katherine Towle, a white woman, and John H. Knox, an African American tailor. Around the age of seven, her father passed away. The cause of his death is unknown. Kittie, her mother, and older brother Ernest then moved to Boston’s West End neighborhood. The area was known for its diverse African American and immigrant populations. Kittie worked as a seamstress to support herself.

Despite having limited financial resources, Kittie pursued her interest in cycling, becoming very proficient in the sport. She joined the Riverside Cycle Club, which was a black cycling club. Knox also became a member of the League of American Wheelmen (L.A.W.) Her membership was contested when, in 1894, the organization amended its constitution to indicate that membership was only open to white members. Despite the status of her membership being challenged, Knox’s popularity, particularly with the organization’s female members, continued to rise. She also received considerable media attention regarding her appearance rather than her cycling skills. Kittie was a formidable cyclist, typically finishing in the top 20% in the majority of her races.

Kittie designed her cycling attire, which drew attention because she chose not to wear traditional cycling attire. She consistently ranked in the top 20% of every race she entered, many of which spanned over 100 miles. Kittie’s exceptional speed and skill on the bicycle surpassed that of most men, challenging established norms in the sport. More significantly, she portrayed cycling as an enjoyable activity rather than a complex social endeavor reserved for the affluent elite. Naturally, her approach unsettled those who benefited from cycling’s exclusivity, both among men and women entrenched in the sport’s elitist culture.

In 1895, Knox was reportedly denied entry to an L.A.W. convening at Asbury Park. She had also encountered discrimination at local restaurants and hotels as well. The controversy prompted the organization to reconsider its “white’s only” policy and affirm its membership with the organization. She was the first African American to be accepted into the organization.

Knox was indeed a pioneer for African Americans and female cyclists. Sadly, her life was cut short when she died from complications related to kidney disease in 1900 at the age of 26. Her mother died soon after, followed by her brother, who died by suicide.

Another installment of melanated mail has been delivered. Ponder, reflect, and pass it on.